Yü Ying-shih saw Hong Kong as beacon of hope for the Chinese-speaking world

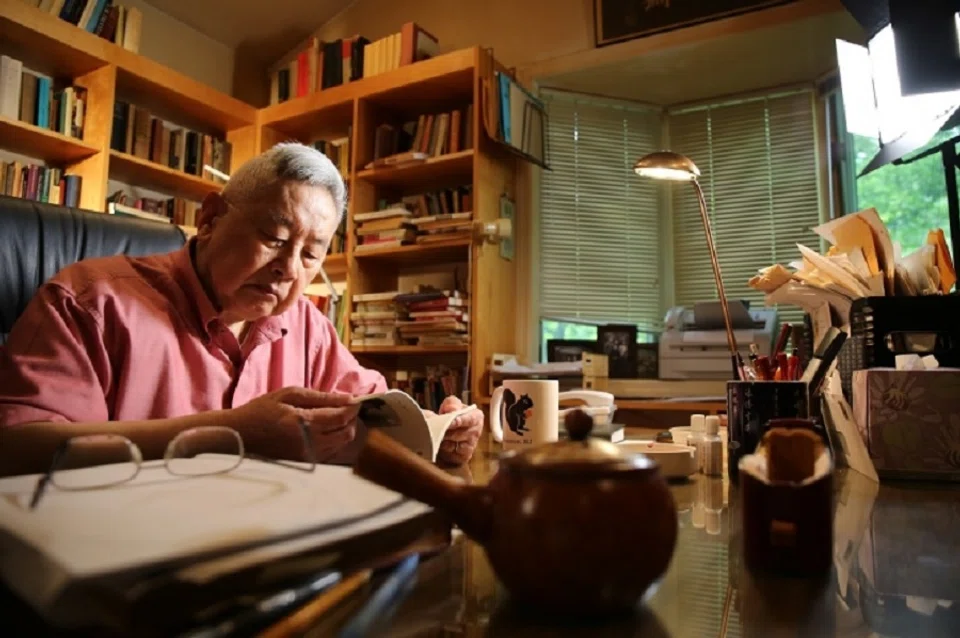

The passing of Professor Yü Ying-shih on 1 August 2021 at the age of 91 has, justly so, prompted an outpouring of reflections on his vast body of scholarship on Chinese cultural history as well as his lifelong commitment as a public intellectual.

More so than anyone from his generation, Yü laoshi (老师, teacher), as he is known to his students, whether formal or informal, has been widely regarded as having embodied the traditional ideal of a shi (士), a scholar committed to not only the highest standard of learning but also, through it, serving the common good by speaking truth to power. Many have endeavoured, of course, but none, at least in the last half-century, it is fair to say, has done so with such authority.

Yü laoshi's central concerns were the characteristics of the evolution of Chinese culture.

There are, obviously, many ways to connect the strands in Yü laoshi's scholarship as a cultural historian of China and his popular writings on contemporary affairs in the Chinese-speaking world. But even though he was, as it should be evident from his first to his very last monograph, deeply interested in the historical developments of other parts of the world, ultimately, Yü laoshi's central concerns were the characteristics of the evolution of Chinese culture.

As a historian, Yü laoshi was especially mindful of turning points, whether they were brought about by external factors (such as the introduction of Buddhism into Han dynasty China) or by what he called the "inner logic" of development. But he also believed that, over time, there had developed within Chinese society a set of core values, a system of beliefs and practices that reflects at once the particular trajectories of China's past and the shared aspirations of humanity.

Throughout his life, Yü laoshi had not shied away from making known his opposition to the Chinese Communist Party.

Despotic party-state at odds with higher instincts of Chinese culture

It is through his conception of this duality of Chinese culture - one that is dynamic and yet persistent - that one could, I think, make better sense of the connections between Yü the scholar and Yü the public intellectual.

Throughout his life, Yü laoshi had not shied away from making known his opposition to the Chinese Communist Party. For him, while the Chinese party-state, especially since the 1980s, might be able to claim some success in economic terms, its anti-humanistic authoritarianism has only deepened with time.

For Yü laoshi, in explaining China, one may be justified to gesture towards certain "Chinese characteristics", but such gesturing would be both shameless and misguided if its ultimate aim is to service a despotic party-state. For Yü laoshi, the stripping of dignity from individuals in the name of the common good, still commonplace in mainland China (see the lockdown in Shanghai for recent examples), is fundamentally at odds with what he considered to be the higher instincts of Chinese culture. To him, the fact that it has to fall on those on the outside to point out so is another clear indictment of the current political system.

That, to the very end, Yü laoshi had maintained a deep interest in the affairs of Hong Kong should not come as a surprise. To be sure, it was in the then-British colony that he spent six formative years (1950-1955) studying with Qian Mu (1895-1990), among other émigré scholars, at the newly-founded New Asia College, and it was at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, two decades later, that he took up the role of an administrator and experienced two of the most challenging years in his academic life.

But Yü laoshi's concerns for Hong Kong were not based just on such personal connections. While he certainly recognised the nature (and harm) of colonial rule in Hong Kong, he had also come to see the British colony as a beacon of hope for the Chinese-speaking world.

Although he continued to view Hong Kong society as primarily driven by commerce, he had come to appreciate, especially following the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989, that, under the cloak of materialism, there was in fact widespread support among the people of Hong Kong - as witnessed through what used to be annual candlelight vigils held at Victoria Park - for freedom, democracy and human rights.

I think it would not be too far off to suggest that, for Yü laoshi, to be Chinese is to be human, and to be human is to be free.

Significance of Hong Kong in the history of the modern world

So even though Yü laoshi might not be entirely familiar with what many would consider to be the distinctive features of Hong Kong - its particular configuration of the Cantonese language, its popular culture, its various forms of hybridity, etc. - he understood very well the significance of the city in the history of the modern world.

Over the past decade, as the reach of the Chinese party-state was becoming more and more intrusive, Yü laoshi had found it increasingly necessary to speak up alongside the students, academics, and other activists in Hong Kong.

For him, the issues at stake were not confined to the harms associated with the particular problems of the day, such as the introduction of national education into the school curriculum (2012), the postponement of universal suffrage (2014), the amendment of the fugitive ordinance (2019), and the promulgation of the National Security Law (2020); rather, the issues, fundamentally, had to do with human dignity. I have not located this specific framing in his writings, but I think it would not be too far off to suggest that, for Yü laoshi, to be Chinese is to be human, and to be human is to be free.

... for Hong Kong to continue to serve as a beacon of hope even in what might seem to be the darkest of times - one should seek to understand its evolution and to embody its best characteristics.

It remains to be said that, to the end, Yü laoshi had maintained that the essence of Chinese culture could in fact be located beyond the land of China (this is how he would like the phrase "Where I am, there is China" to be understood). But while he did consider himself to be an (not the) embodiment of Chinese culture, he had made it his lifelong endeavour to understand its continuities and transformations.

So even though it was not Yü laoshi's modus operandi to tell others what they should do or how they should think, it would not be wrong to infer that, for Hong Kong to be wherever one is - for Hong Kong to continue to serve as a beacon of hope even in what might seem to be the darkest of times - one should seek to understand its evolution and to embody its best characteristics.